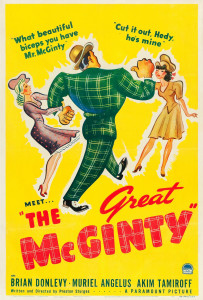

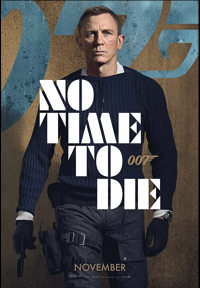

After a quick survey of some recent releases, including No Time to Die and The Card Counter, Jeff Godsil, from down in Los Angeles, discusses Preston Sturges's The Great McGinty, while Britta Gordon reflects on South Korea's 2017 Claire's Camera, and in the book corner, a new monograph on John Frankenheimer's Seconds.

Seconds, released in 1966, and directed by John Frankenheimer from a novel by John Ely adapted by Lewis John Carlino, was the third and final film in his “paranoia” trilogy, which began with Seven Days in May and continued with The Manchurian Candidate. May still holds up beautifully, and Manchurian is an odd film with its own pleasures, but Seconds was a difficult project that failed at the box office for reasons that Jez Connolly and Emma Westwood address in their new monograph in the Constellations series from Liverpool, “Studies in Science Fiction Film and Television,”which also publishes the Devil’s Advocates series.

For one thing it starred Rock Hudson as the second integration of a middle-aged banker recruited by a company that gives its clients a new lease on life. Those who wanted a Rock Hudson sex comedy were disappointed, and those who wanted a science fiction film didn’t want to see Rock Hudson in it. As the authors declare:

If ever a film deserves a second life, it is Seconds, director John Frankenheimer’s criminally overlooked monolith of bleak paranoia. Part science- fiction-of-the-speculative-present persuasion, part proto-body-horror, part noir-thriller- cum-black-comedy, a film that is locatable at the thematic and stylistic intersection of the post-McCarthy mindset, European art cinema, the suburban identity nightmares of The Twilight Zone and the mid-life crises of malehood aroused by 1960s counterculture. Seconds is a film that pushes into parallel definitions and bullheadedly refuses to be described in 25 words or less.

They go on to note that:

A significant influence on Seconds preceded it by ten years and can be found outside the genre. The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit (Nunnally Johnson, 1956), based on the hit 1955 novel of the same title written by Sloan Wilson, struck a chord, and perhaps a nerve, among America’s middle class, male white-collar workforce with its story of the prototypical discontented businessman and the strain of executive conformity. It encapsulated a particular anxiety and through its drama raised the fundamental question on the mind of many a working man trapped in the mechanism of the American Dream: who am I? As the decades turned and the Cold War chilled, that managerial anxiety fused with the prevailing countercultural reaction to living in the shadow of the bomb and a fresh version of that question came to be asked: who do I want to be?

They had how much the film anticipates the ’70s, but also the ‘80s.

The idea of the shadowy organisation controlling individuals without their knowledge would rapidly become a standard element of much science fiction cinema in the 1970s and 1980s, representing a growing awareness of and disaffection with ruthless, dehumanising capitalism. Think of the Spectacular Optical Corporation in Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983), Weyland-Yutani in Aliens (James Cameron, 1986) and Omni Consumer Products in RoboCop (Paul Verhoven, 1987) and you can see how the notion of the sinister corporation took off as the prevailing antagonist in the genre. For this author, to know Seconds is to fully understand a fascinating and important cultural cataclysm that occurred in the mid-20th century, one that took place before she was born. Seconds acts as a capsule distillation of this seismic shift, in which patriarchy in all its guises– political, corporate and social – experienced its own mid-life crisis and, as a result, the very pillars of society became noticeably unstable.

This is one of the best books on a single film that I’ve read in a long time. For one thing, it is endless allusive and referential, shows wide learning and media understanding, constantly surprises, and makes fascinating connections. For example:

Aside from the Saul Bass credits, Seconds shares with Psycho a narrative trajectory that can be likened to the human digestive system. Consider the post-credits opening sequence of the Hitchcock film; an aerial shot of the city of Phoenix that enters the mouth-like window of a hotel room and comes to rest on the sandwiches by the bedside of the lovers, Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) and Sam Loomis (John Gavin), during their illicit lunchtime tryst. The symbolic mastication of this first love scene serves to break open and extract the film’s starter exposition – the couple’s passionate desire to be together constrained by their lack of money

And finally:

The means by which the Company embroils its clients is a disinfected variation of the Oldest Profession. It is essentially a colossal, elaborate escort enterprise, promising physical, emotional and – by extension – sexual freedom and pleasure yet, ultimately, delivering torment and treating the customer as commodity, pound for pound. The corporate costumes merge: executive suits, surgical scrubs, butchers’ aprons. The business premises loop and interlace; slaughterhouse, beach house, charnel house. Company clients are always usable body parts, from start to finish; weighed, measured, processed.

There is so much more that could be quoted from this slim but dense book, one that makes you not only want to review Seconds, but the other Frankenheimers in the paranoia series, but re-see those from the ’70s that it anticipated, such as The Parallax View, The Conversation, Night Moves and so many, many others.

- KBOO